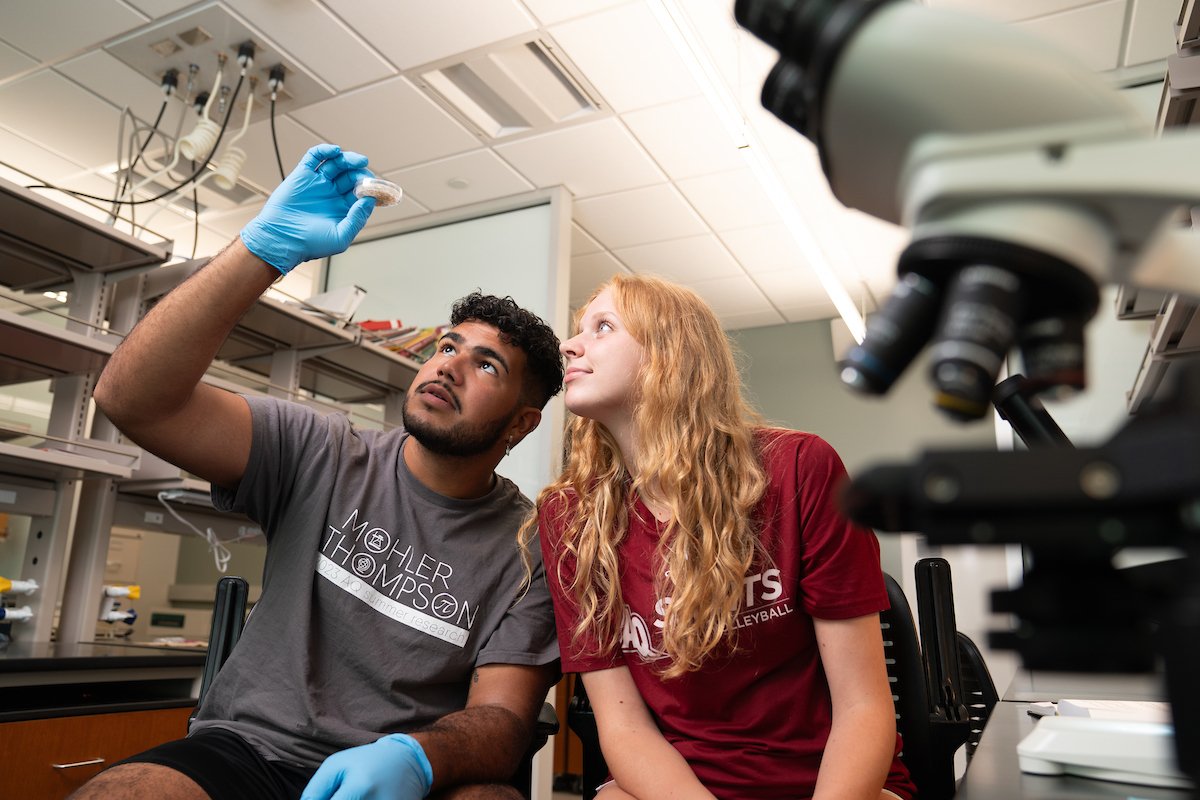

This summer, a few new creatures have taken up residence in the labs of Albertus Magnus Hall under the care and supervision of senior biology major and math minor Ernesto Lopez, freshman biochemistry and molecular biology major Alyssa Detweiler and biology professor Dr. Rob Peters. Ranging in size from just barely visible to an inch and a half in diameter, several sea anemones are the subject of their summer research.

The anemones, which Lopez and Detweiler affectionately refer to as “their babies,”

are hand fed tiny shrimp in their tank which sits on a sunny windowsill in the lab.

The students can even tell when the anemones are happy or disturbed based on the posture

of their tentacles. They close up when something is off about their environment.

The anemones, which Lopez and Detweiler affectionately refer to as “their babies,”

are hand fed tiny shrimp in their tank which sits on a sunny windowsill in the lab.

The students can even tell when the anemones are happy or disturbed based on the posture

of their tentacles. They close up when something is off about their environment.

Lopez, Detweiler and Dr. Peters' are researching “Molecular Interaction in Cnidarian Dinoflagellate Symbiosis.” For those of you in the audience who do not have a background in marine biology, let’s break that title down.

Cnidarians are a group of invertebrates including anemones, corals, and jellyfish. They’re all aquatic and they form a unique symbiotic, or mutually beneficial, relationship with a type of algae, like the green stuff on your ponds, called dinoflagellates. The algal cells produce energy for the cnidarian through photosynthesis.

“The algal cells live inside the cnidarian cells, so it's in some ways a more physically intimate relationship and a little more unique form of symbiosis,” said Dr. Peters.

When this relationship is disrupted due to stress in the environment, the colorful algal cells exit the cnidarian cells, and it leads to a big problem: coral bleaching. The issue has multiple contributing factors and the world's coral reefs could soon disappear as a result.

“Bleaching also happens in anemones,” said Detweiler. “We want to look at the relationship between the algae that lives inside their cells and the anemones so that we can learn more.”

Because coral and anemones both form this symbiotic relationship with algae, research into anemones can also help us understand coral reef bleaching. However, there are still many unanswered questions about how that relationship is controlled at the cellular and molecular level.

“We want to know about the scavenger receptor, and if it has anything to do with this linking,” said Lopez. “No one has ever cloned this gene and published the sequence. That’s what we’re hoping to do and then hopefully it will open doors for other scientists.”

As they conduct this research, Lopez and Detweiler are also learning about their own interests and what they want their futures to look like. They’re growing more confident in their abilities and confirming their love for the lab.

“I was a freshman when I applied for this and I had no idea what I was getting into,”

said Detweiler. “To get the opportunity to do a lot of this stuff is exciting, and

it's what I want to do in the future. It feels like a really solid step into my career,

and honestly, it's really enjoyable.”

“I was a freshman when I applied for this and I had no idea what I was getting into,”

said Detweiler. “To get the opportunity to do a lot of this stuff is exciting, and

it's what I want to do in the future. It feels like a really solid step into my career,

and honestly, it's really enjoyable.”

The two students have learned to run agarose gels, do PCR reactions, work thermocyclers and more. They’re picking up real world skills, and Dr. Peters is delighted by their work and enthusiasm.“Ernesto is taking great care of the anemones,” said Peters. “They're looking really healthy, and they're reproducing. And every time we have an experiment that works, the students get excited. I love that.”

As a senior, Lopez wanted to let other students know it is never too early to get involved. From joining student organizations to applying for research opportunities, it’s never too early. “ I would do it again if I could, but I'm graduating,” said Lopez of his experience in the lab with Detweiler and Peters. “Just take as many opportunities as you can, especially if they're being offered right there in front of you.”

The Mohler-Thompson Summer Research Program was established in 2007 thanks to donations to an annual grant by the Mohler and Thompson families. Their generosity allows students and professors to collaborate on cutting edge research in their respective fields. Aquinas College and the Mohler-Thompson Researchers would like to thank the Mohler and Thompson families for their commitment to advancing our understanding of the world through research.